Hidden Mother discussed by Lauren Collins in the New Yorker:

In the Victorian era, mothers weren’t exactly doing it for the ’gram, but they still had to work for the photographs they wanted. The long exposures required by old-school cameras meant that young children needed to be kept still for considerable periods of time. Studio photographers enlisted mothers as literal supports, camouflaging them in sheets and drapes so that they could prop up their offspring inconspicuously. Alternatively, a photographer might scratch out a mother’s face in postproduction or blot it out with black paint.

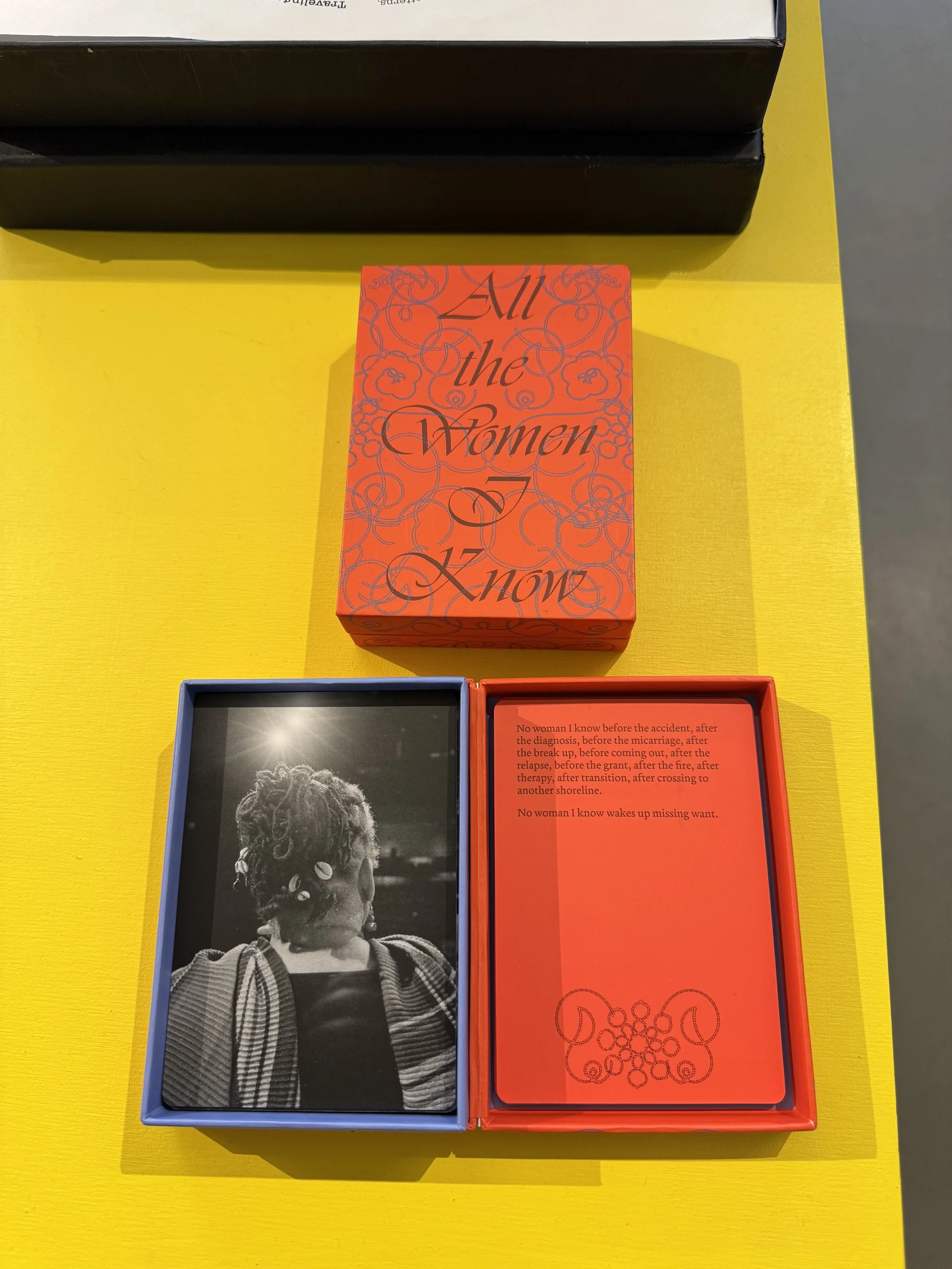

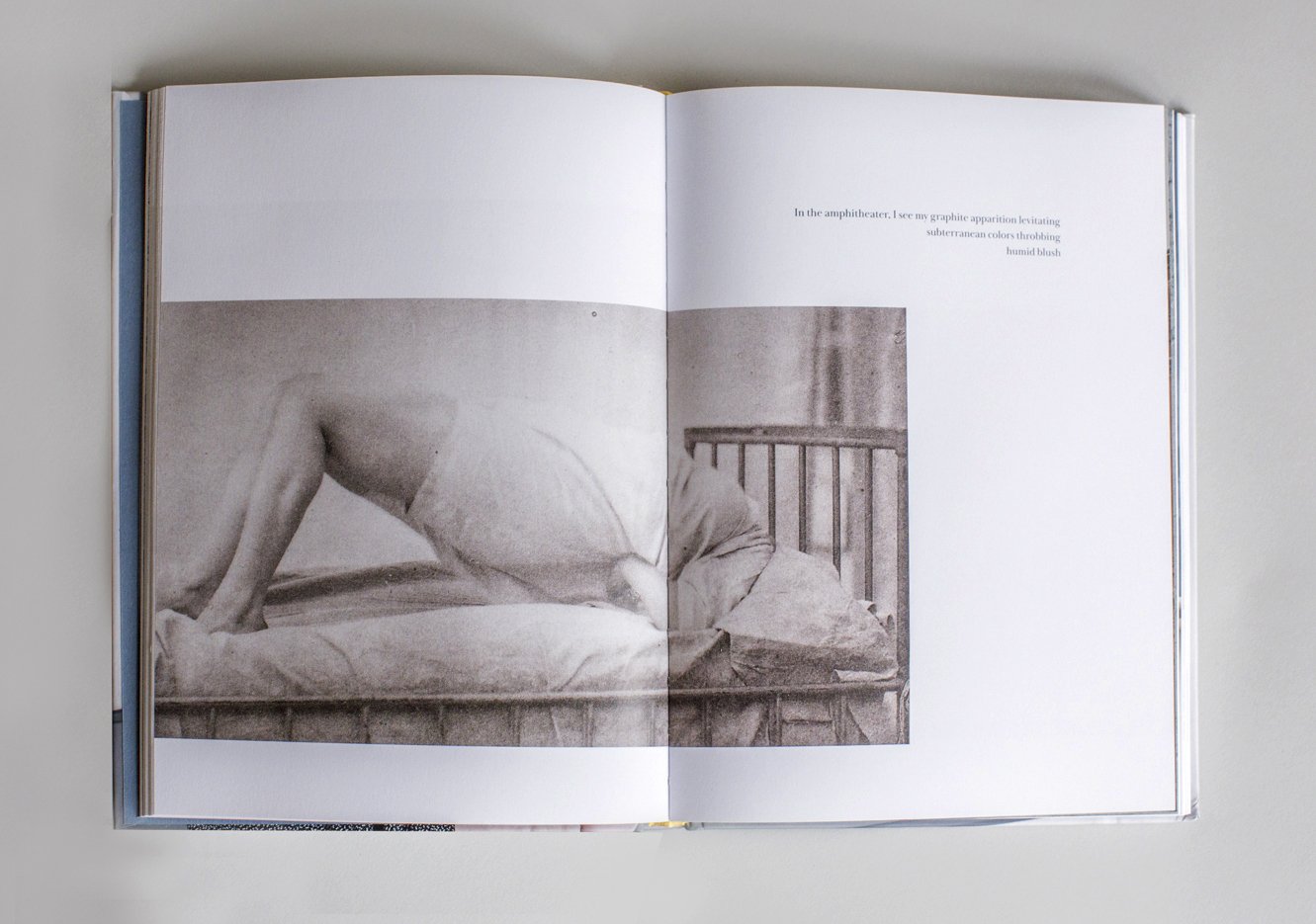

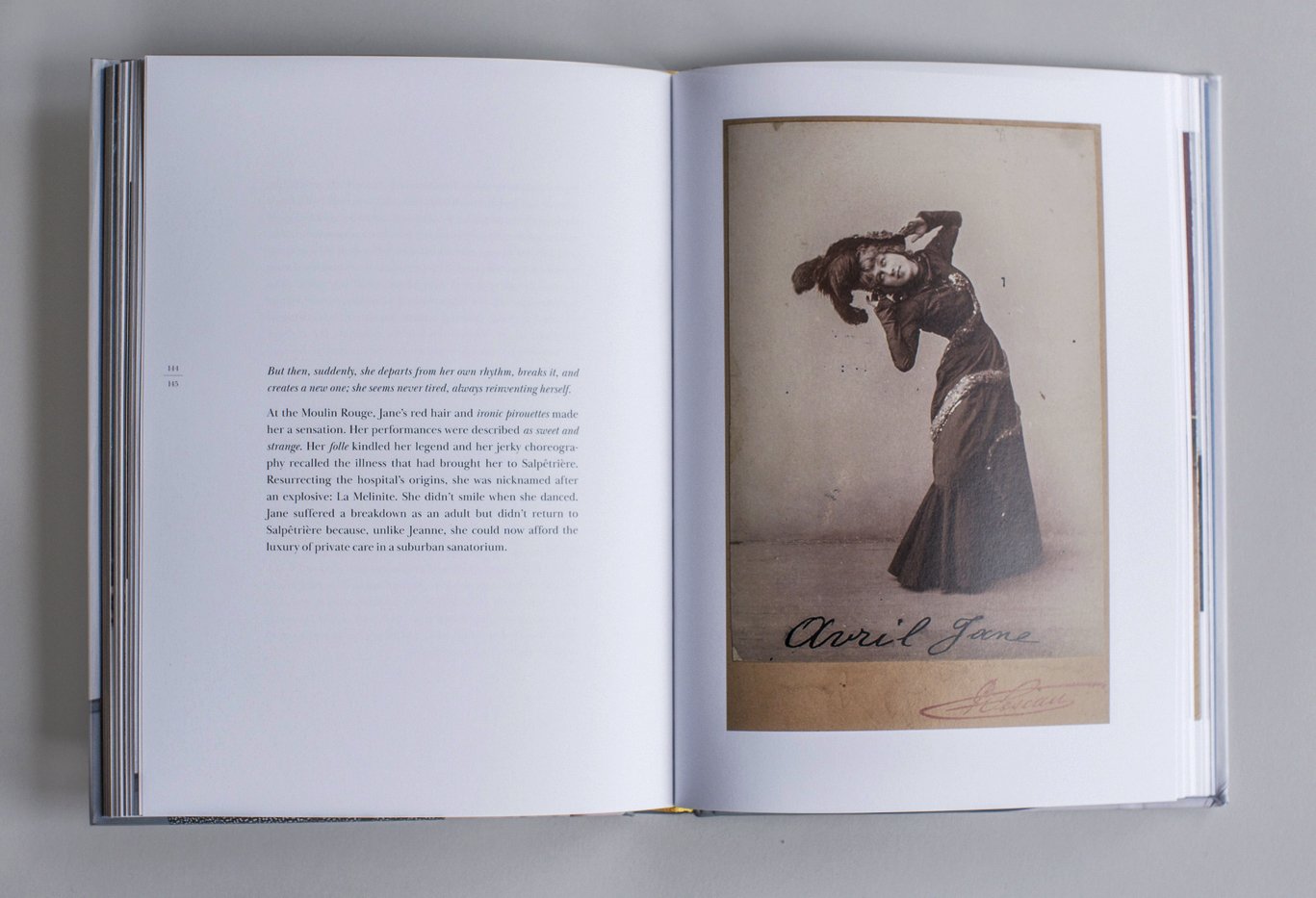

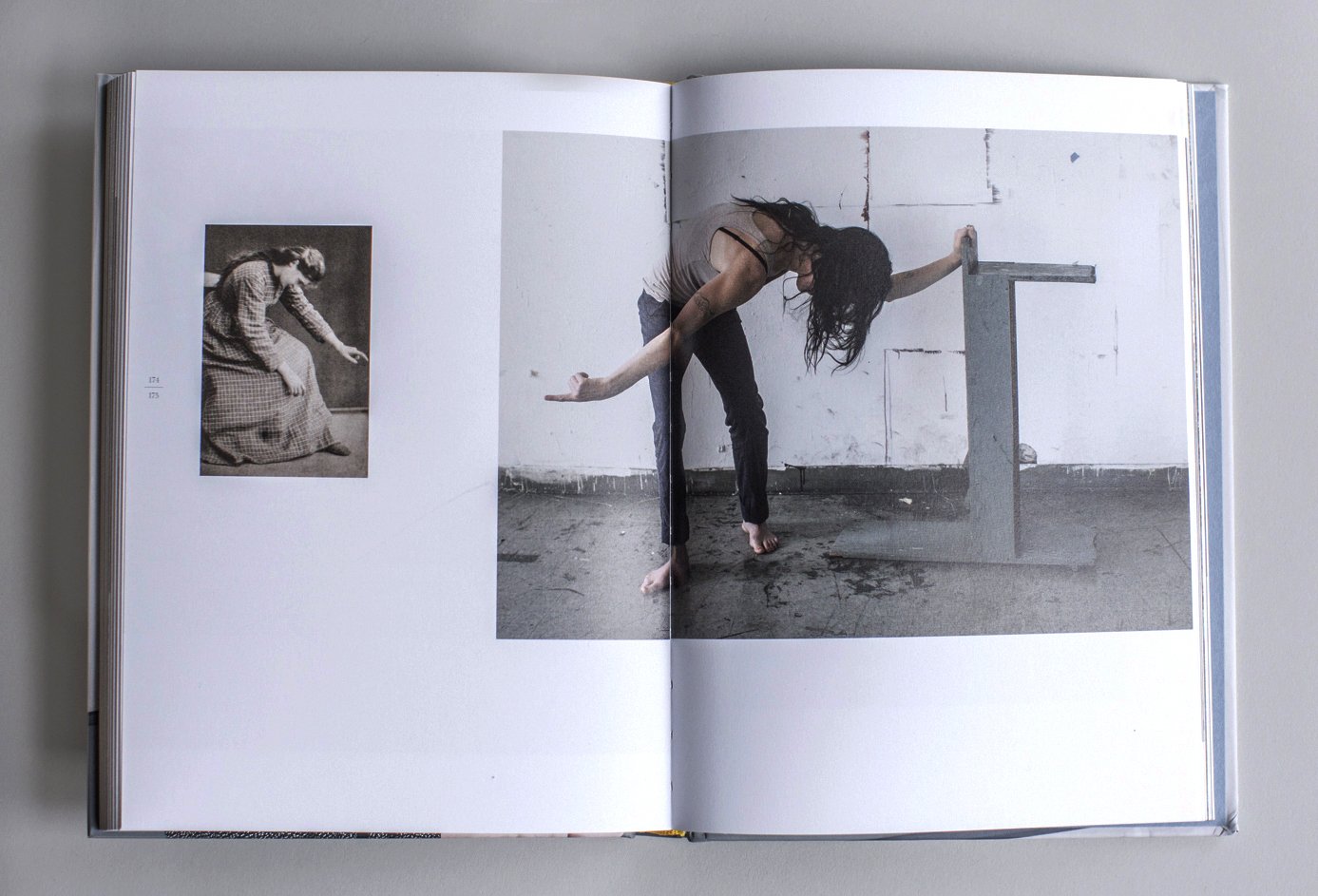

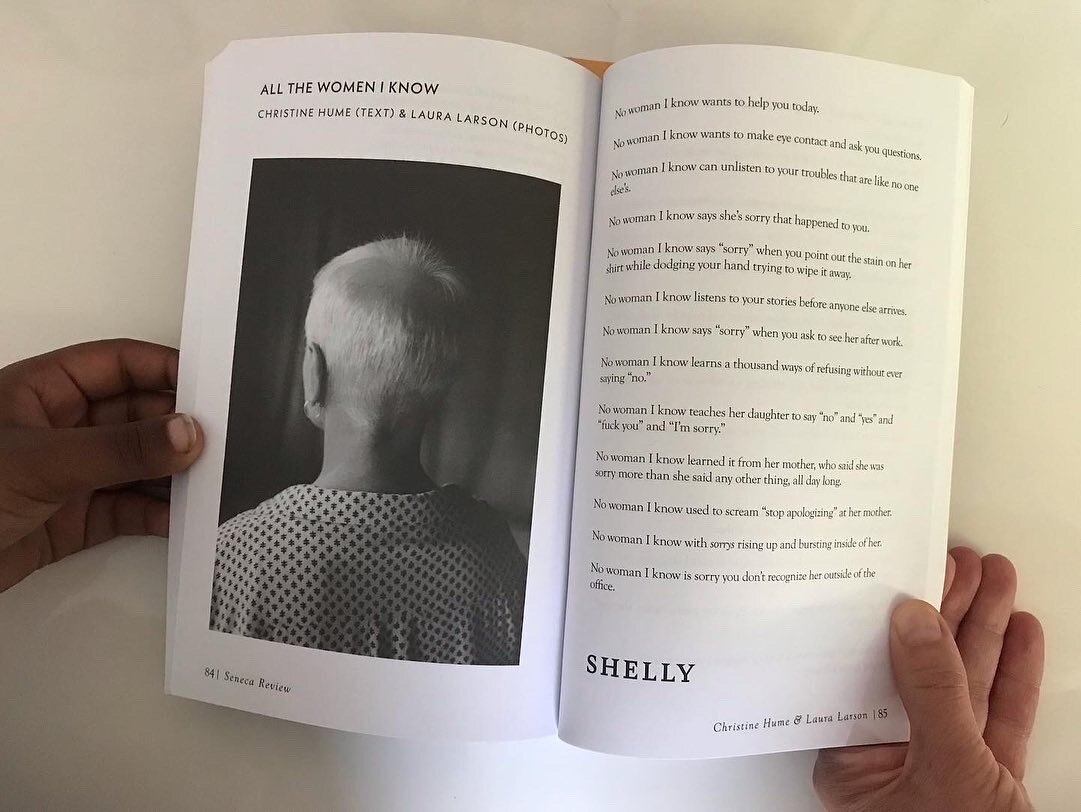

The photographer and scholar Laura Larson collects many of these images in Hidden Mother, a haunting book from 2017 that mixes monograph and memoir. (She became interested in the subject during the process of adopting a child.) “The hidden mother appears in many forms, playing a structural but visually peripheral role in these portraits,” she writes. “Her form becomes indistinguishable from the appointment of the scene.” The mothers are uncanny, even darkly comic. They bring to mind vestals, or ghosts in a low-budget horror movie. They are human furniture, upholstered in black alpaca or a taffeta check. In one memorable image, a baby in a white diaper reclines on what appears to be a floral-print chair. A disembodied hand, fingers poised in supple anticipation, emerges from the left armrest. Describing such scenes, Larson writes:

A tattersall tablecloth, now embroidered; a flowered scarf; a striped blanket; a brocade drape (leaf, twig, vine, coralene); a calico curtain; a crocheted shawl; a velvet swathe.

She smells his hair.

She sees through the lace.

Her body’s uncomfortable, a little impatient, listening for the click of the lens closing.

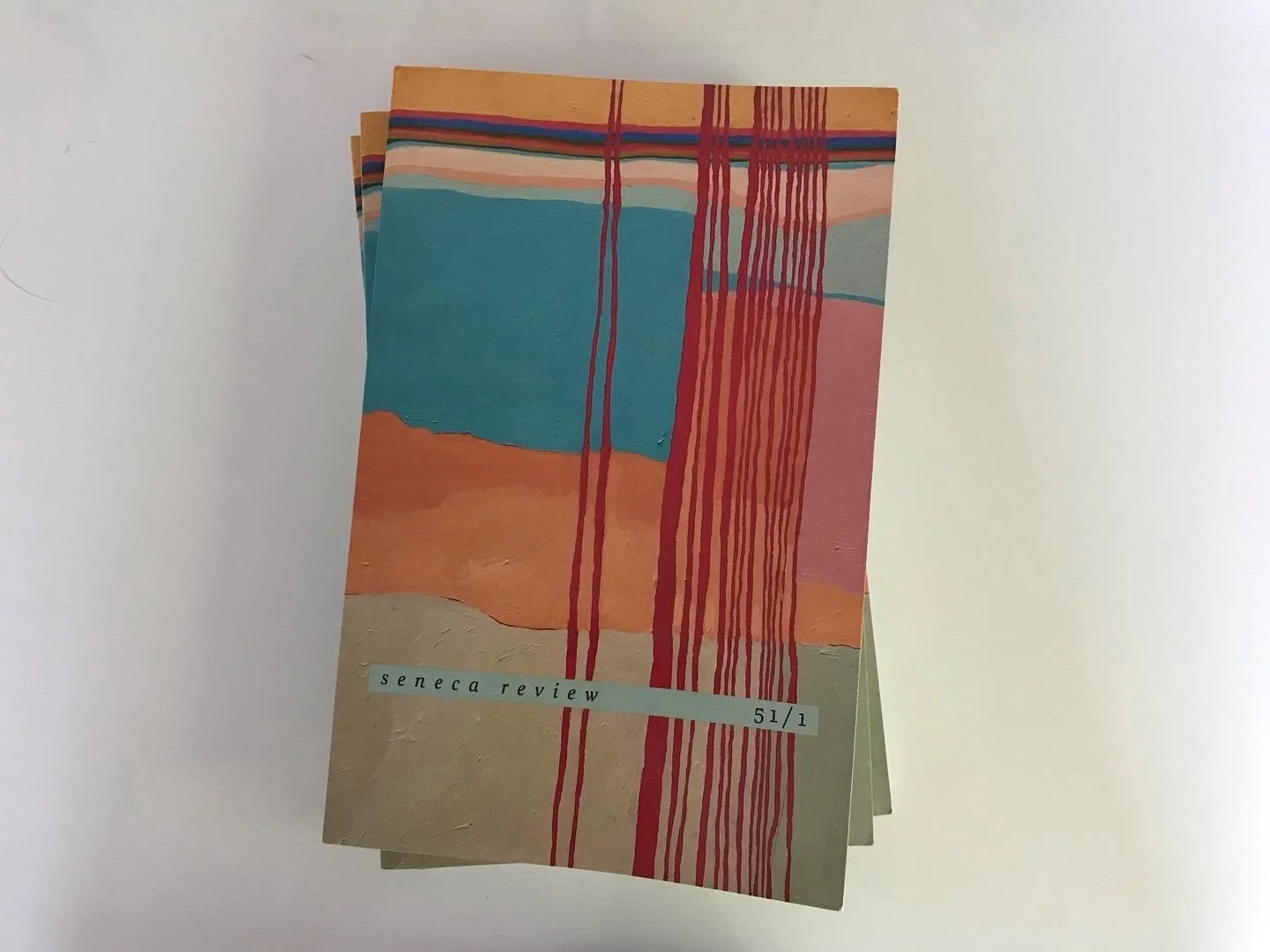

The first edition is close to sold out! Order your copy here.